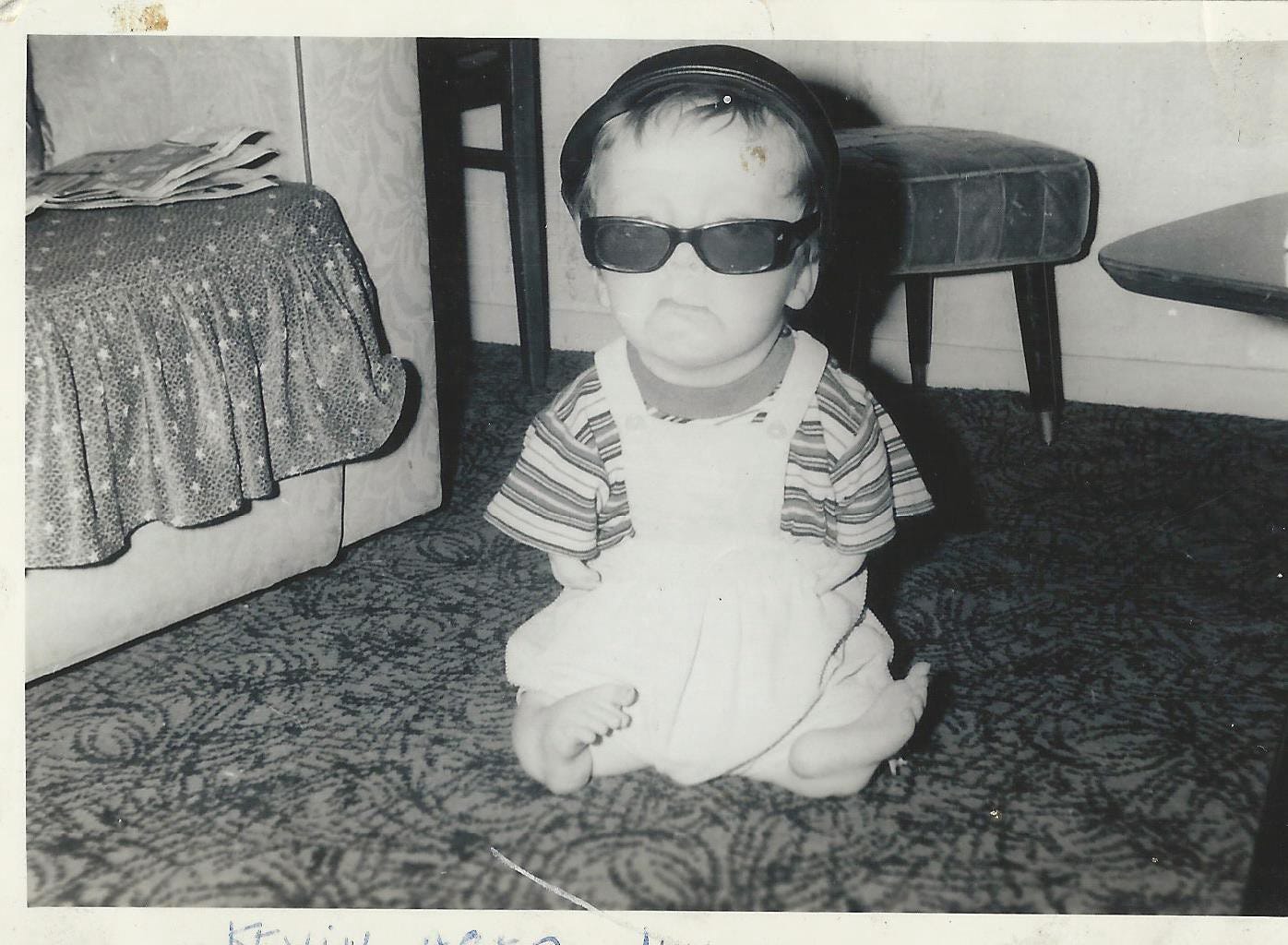

Throughout my life, when strangers first saw me I was met with a variety of countenances, ranging from disgust to wonder. In between there are also looks of curiosity, pity, sadness, wariness, surprise, even fear, but sometimes also tenderness, warmth and even admiration. Rarely have people looked bored or indifferent. Viewed as either a tragic or heroic figure. Useless and incapable or conversely, resilient and brave. Of course, it may all have been my imagination, or insecurity, but I know from lifelong experience it probably isn’t.

People usually clock my powered wheelchair first which often defines, in an instant, their whole perception of me. They assume they know me just from the object that they see me sitting in or driving. Some people studiously look away as if they are afraid I might engage them in conversation, or some might enthusiastically grab my attention and greet me as a long lost best friend [the latter especially applies to people who are drunk].

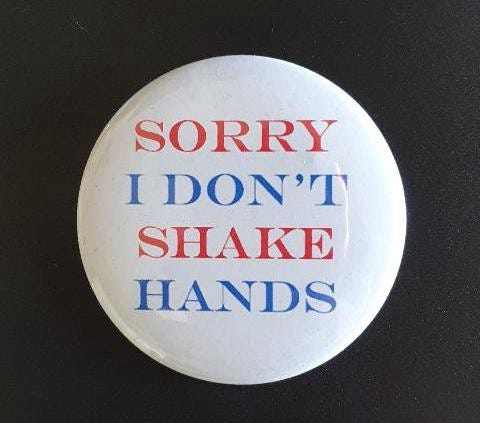

Shaking hands was always a minefield of uncertainty, both for myself and others. I’d confidently hold out my right hand and some would deliberately ignore the gesture, some would bypass my hand altogether and either pat me on the head [urgh] or tap me on the shoulder and a few would tentatively touch a finger very gently lest I would shatter into tiny pieces like a delicate porcelain figurine [I do actually have a lot of strength in my short arms and in my younger days I could hold my whole body weight with them, hanging on a low bar in the school gym]. Very rarely did I get a firm or enthusiastic handshake. In the end I stopped offering my hand unless the other person initiated the greeting. I generally just give a slight nod now.

One tiny blessing of this damned Covid pandemic was the fact that everyone stopped shaking hands. I dug out an old badge that I’d never worn and during the lockdown I put the photo of it on my Facebook page with the words ‘I just KNEW this badge would come in handy one day. Not that I’m going out ANYWHERE.’

When I talk about my life, in universities, schools or at conferences etc I see some of these same reactions from my audience. I begin by talking of early negative assumptions and low expectations that were made about me from my early days [many of which persist to this day]. By the end of the lecture I have, hopefully, overturned all those negative assumptions, ideas and stereotypes of disabled people. The audience certainly always goes away with a different idea about me, moving on from their initial judgements solely based on the fact of my being a wheelchair user.

In some ways, this is also the purpose of my autobiography. I’ve never set out to be inspirational at all, I’ve just got on with my life, but if some readers do feel inspired then fine. I hope I come across as optimistic — the one thing I hate is people feeling sorry for me. Like everyone, my life has had its ups and downs, its challenges and misfortunes. But generally, I’ve been incredibly lucky — both in terms of the support I have had from my family, my friends and colleagues, but also in terms of my achievements and breaking down some of the barriers that blocked my path along the way.

Disabled people all have different stories to tell and many Thalidomiders have written autobiographies or had biographies written about them. We might all share the same medical label for our varied physical or sensory impairments but that’s about as much in common that most of us have with each other. Of course, like other disabled people, we all face the same challenging barriers that society throws up, despite the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 and the Equality Act 2010, which did improve our lives, there is still a long way to go to make our world fully inclusive.

One thing almost all of us experienced though, from the moment of our birth, was being written off as failures, without any realistic expectations of having a prosperous future or even a life worth living. In the 1960s society had a very negative attitude towards any kind of impairment ~ in my Disabilities and Equality lectures I list in my PowerPoint presentation a variety of negative words and assumptions that were frequently used to describe me in the media, many of these even adopted by professionals in the medical, educational or social services fields.

This negativity towards disability was so widespread and ingrained within society and within our culture — many of the characters in literary fiction and portrayed in films included villains and baddies that were often deformed or crippled in some way. It therefore isn’t surprising that even my own mother absorbed this negativity and thus reflected these attitudes.

I don’t completely blame Mother as she was simply a product of her generation, she took on all the medical advice that she had been given and she genuinely wanted to protect me. Her motives were well meaning, but nevertheless, she was totally wrong on everything she said about me in the newspapers or on national television. Mother could never, even in her wildest imagination, have predicted how my life would actually turn out.

Over 400 ‘Thalidomide babies’ survived their first year in the UK, but in fact nobody really knows the true figure of those who didn’t. There were definitely more, unrecorded, deaths. To be blunt, there is irrefutable evidence of a euthanasia policy in the NHS in the 1950s and 60s — ‘unofficially’ of course.

In the Canadian documentary film ‘No Limits: The Thalidomide Saga’ (2016) [1] by Emmy-winning Director John Zaritsky, the former Director of the Thalidomide Trust, Dr Martin Johnson states:

“It is unquestionable that midwives and doctors were killing disabled children in the hospitals, in the delivery rooms on a large scale in Britain, in Germany and if there then probably everywhere else.”

This is followed by an old newsreel from British Pathé News:

It is quite extraordinary that a baby girl was murdered just because she was born without arms and that her parents and three other accomplices, were acquitted and the verdict celebrated in the world’s news media!

As Dr. Johnson stated, unofficial euthanasia was practiced on a wide scale in NHS hospitals throughout the UK concerning disabled babies. ‘Nil by mouth’ signs fixed to the cots of crying newborns was not uncommon. Disabled babies, abandoned and unwanted, were often deliberately starved to death.

Let me be clear. The National Health Service, a public funded service offering the best healthcare to every citizen in the United Kingdom, entirely free at the point of need to all, established in 1948 by the radical postwar Labour government [the Conservative party voted en masse to oppose it] was the best thing to happen to this country. The NHS has saved my life on several occasions and quite frankly if I had lived in a country without free health care [such as the USA] I’d be dead or destitute right now. It isn’t perfect and successive governments have grossly and shamefully underfunded it, but I and millions of others, feel passionately protective of the NHS and will fight tooth and nail to keep this cherished and critically vital institution.

But history shouldn’t be whitewashed or rewritten however unpalatable and shocking it may be. A few years ago the popular BBC drama ‘Call the Midwife’ about a group of midwives working in the East End of London in the 1950s and 60s featured the Thalidomide medical disaster in several of their episodes. The most moving episode by far featured the euthanasia of a thalidomide impaired baby. The baby girl had almost identical deformities that I have — all four limbs missing with hands attached to the shoulders with missing fingers and feet attached to hips, minus her legs. The mother abandoned the baby [2] in the hospital and a nurse place the disabled girl on a sill in the sluice room with the window wide open on a cold winter’s night to die of hypothermia. This was extremely brave of the producers of the programme to show this (I believe that they consulted with lawyers first) — but it was accurate, history not whitewashed or rewritten. I was really moved watching this episode. The ‘baby’ was a prosthetic doll but it was incredibly detailed and life-like, with moving lips, eyes, nostrils, fingers etc. It looked so realistic and so similar to my impairments and body shape.

I know I have been critical of my late mother in much of my writing, but I will always be eternally grateful to her for not abandoning me in that maternity hospital in Walton, Liverpool. I could have easily become one of the many unrecorded dead victims of the thalidomide drug and a health system that deemed ‘severely’ disabled humans as having lives not worth living.

Thank you Mother.

[1] You can see the full documentary here on YouTube — you might be relieved to know that I don’t feature in this one, but it is a brilliant and moving film which accurately details the Thalidomide story.

[2] I pass no judgement on parents who abandoned their newborn babies. They received no counselling to discuss options or support for the trauma of having an imperfect child — in fact they were often encouraged to abandon their disabled children in the hospitals, such was the stigma around disability. I’m just so grateful I had a loving and supportive family and relatives.

________________________________________________

On my website kevindonnellon.com is a PayPal tab and I will be extremely grateful for any contribution towards me finding an editor and publisher etc to get my autobiography out there. Thank you!

Many years ago, I was walking along Wandsworth Hight Street, on my way home one afternoon (I think I was bunking off school) and crossing the road I came face to face with a man who had a really deformed face and it shocked me and he saw my reaction and confronted me. I can't remember the details of the conversation except I felt so ashamed and embarrassed by my reaction but he commiserated with me and said my reaction was typical and normal. I think I apologised, we shook hands and we went on our way.